My An Arkie's Faith column from the January 26, 2022, issue of The Polk County Pulse.

On the mornings that I pick up my auto glass order, the alarm rings at 4:30 A.M. I never worry about the alarm going off. My cell phone knows what time it is and always wakes me up, even if the electricity has been off during the night. But it hasn’t always been so easy to measure time.

Before medieval times, humans measured time with oil lamps, candles, water clocks, and sundials. By the mid-14th century, large mechanical clocks began to appear in the towers of several cities. These clocks were not very accurate. Christiaan Huygens made the first pendulum clock in 1656. His timepiece had an error of less than 1 minute a day, and his later refinements reduced his clock’s errors to less than 10 seconds a day.

Even so, time measurement was still haphazard in the 19th century, with time being kept differently in each community. In the United States, there were over 140 local times in 1883, resulting in slight time differences between adjacent towns and cities. That year, major railroad companies in the U.S. began to operate on a coordinated system of four time zones. It was not until 1884 that a conference at Greenwich reached an agreement on global time measurement and adopted Greenwich Mean Time as the international standard. The world was beginning to get a handle on standardized time.

But it still wasn’t easy to coordinate with Greenwich Mean Time. One enterprising London family had a solution. Every Monday, Ruth Belville stood at the entryway of a London watchmaker. Ruth was in the unusual business of selling time with her watch named Arnold. When the door opened, the storekeeper greeted the weekly visitor with “good morning, Miss Belleville, how is Arnold today.” Ruth replied, “good morning. Arnold is one-tenth of a second fast.” Then she reached into her handbag grabbed a pocket watch and passed it to the watchmaker. He used it to check the store’s main clock and then returned the pocket watch to her.

Once a week, Ruth would get up early and take the three-hour journey from her cottage west of London to the Greenwich Royal Observatory, reaching its gate by 9:00 A.M. She rang the bell and was greeted by the gate orderly who formally invited her inside. There she would hand over her watch, Arnold, to an attendant. The officials compared Arnold to the observatory master clock, then returned the timepiece to Ruth with a certificate stating the difference between its time and their central clock. Ruth walked to the Thames and caught a ferry to London with the official document in her hand. She then began making the rounds, visiting her customers.

The Belville family fell into this business accidentally. In the 1830s, Ruth’s father, John Belleville, worked at the Greenwich Observatory as a meteorologist and astronomer. The observatory leadership grew frustrated by the many interruptions caused by local astronomers desperate to know the precise time for their observational work. Instead of having unannounced visitors coming to the observatory and disrupting their scientific activities, they devised a plan to bring the time to those who needed it. They gave John Belville the task of providing time to nearly 200 customers using a very accurate timepiece that he nicknamed Arnold.

Arnold was formerly known as John Arnold number 485 and named after its maker. It was a highly accurate pocket watch built in the late 1700s. John Arnold originally designed Number 485 as a gift for the Duke of Sussex. The Duke thought the timepiece was too large and refused it. The watch ended up at the Greenwich Observatory. When John Belleville started the time service, he used the most accurate portable timepiece available, John Arnold number 485. In 1892, the watch was passed down to thirty-eight-year-old Ruth, who continued the family business until she was 86 years old.

When Ruth and Arnold were retiring from the time business, a clock was installed in the United States that consistently drew a crowd. In 1939, New Yorkers headed downtown to get the precise time at 195 Broadway in Manhattan. The art deco clock sat in the window of the AT&T corporate headquarters. It was not just any clock; it was the most accurate public clock in the world. A unique piece of quartz crystal provided its accuracy. Every day, hundreds of pedestrians stopped in front of the clock and held their finger on their watch stem waiting for the sweeping second hand to reach the top so they could set their watch accurately. Quartz clocks and watches were sold in large quantities during the 1970s when technological advances made them affordable.

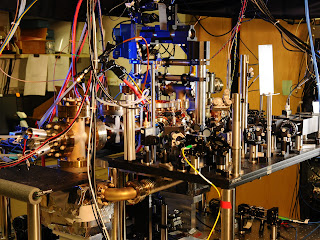

But before long, there were even more accurate clocks. Lord Kelvin first suggested using atomic transitions to measure time in 1879. Louis Essen and Jack Parry built the first accurate atomic clock in 1955 at the National Physical Laboratory in the U.K. Atomic clocks are highly accurate with an error of only 1 second in one hundred million years. Today we can all have the accuracy of an atomic clock by purchasing a clock that automatically synchronizes itself to the atomic clock in Boulder, Colorado.

Why do we place such emphasis on measuring time? Some 200 years ago, Benjamin Franklin wrote, “Dost thou love time? Then use time wisely, for that’s the stuff that life is made of.” Being able to measure time helps us to use it wisely. Because of the fragile nature of time, Moses prayed, “So teach us to count our days that we may gain a wise heart.” Psalm 90:12 (NRSV) That is another way of saying it is the use, not the length, of our days that counts.

Gentle Reader, there are many inequalities in life. But when it comes to the amount of time you have, everybody falls into the same category, and there is perfect equality. Every day, twenty-four hours, no more or no less, is given to every person. The way we use our time is essential. “Be very careful, then, how you live—not as unwise but as wise, making the most of every opportunity, because the days are evil.” Ephesians 5:15,16 (NIV) The great thing about the nature of time is that it is entirely ours to do with what we will. We can, right now, decide to make the best use of our time. May you find peace, joy, and purpose in the ways you spend your time today.

No comments:

Post a Comment